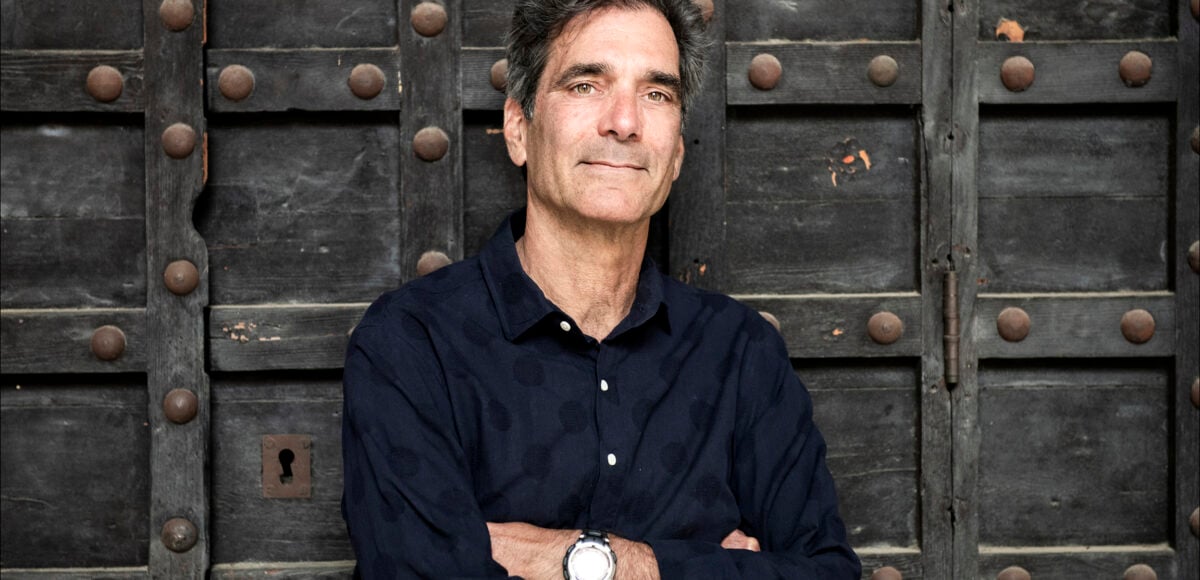

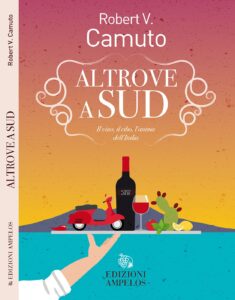

Robert Camuto, award-winning journalist, travel writer, and correspondent from Europe for Wine Spectator, explores Southern Italy in his last book South of Somewhere: Wine, Food, and the Soul of Italy (University of Nebraska Press), just in Italy with the title Altrove al Sud, il vino, il cibo, l’anima dell’Italia (Ampelos, 2022).

In his firs book, Palmento – A Sicilian wine Odissey, Camuto takes us on a journey thorough the rising wine scene in Sicily, the land of his ancestors. In Altrove al Sud, the author uses wine as the driving force to paint the soul of Southern Italy-from Campania to Sicily- and to highlight the generational change brought about by young, smart entrepreneurial winemakers.

In his firs book, Palmento – A Sicilian wine Odissey, Camuto takes us on a journey thorough the rising wine scene in Sicily, the land of his ancestors. In Altrove al Sud, the author uses wine as the driving force to paint the soul of Southern Italy-from Campania to Sicily- and to highlight the generational change brought about by young, smart entrepreneurial winemakers.

Both memoir and travelogue, Altrove al Sudfeatures stories of winemakers, tales of food, reflections on Southern Italian culture, and personal memories. The author depicts Italy in a vibrant and descriptive style that is drenched with passion. In this interview for Wine in Sicily, Robert Camuto discusses the book, the new generations of Southern Italian winemakers, and what wine means to him.

This is a golden age for wines. We are witnessing a slow but consistent growth in the number of native Southern winemakers, oenologists and agronomists (and visionary entrepreneurs) who are not leaving for other countries or other parts of Italy but staying in the South to pursue excellence. This is a revolution – comments Camuto.

The author will discuss Altrove al Sud at the Consortium of Sicilia DOC’s events at Vinitaly on Sunday, April 10th – 16.00 – 16.30 – Pavillon 2, Conference area B 20. The author will discuss his last book within the Consortium of Sicilia DOC’s events at Vinitaly

Sunday April 10th – 16.00 – 16.30 – Vinitaly – Pavillon 2 Sicily, Conference area B 20 – Verona

Tuesday April 12th – 17.30 – 18.30 – Signorvino / Corso Porta Nuova 2/A – Verona (Press Only – invitation)

Your book, “Palmento”, highlighted the emerging wine scene of Sicily and Mount Etna. In this work, you go back to the South with “South of Somewhere” (Altrove al Sud) focusing on the new winemaking generation and their search for a new chapter for excellence [Sicilian wines]. What do these protagonists have in common beyond the fact they are all southern winemakers?

For almost 20 years my wine writing has been about generational change— the “grande bellezza” of young, smart winemakers who are looking back to the traditions of their grandparents and their territory with new sensitive and educated eyes, exploring those places and looking to valorize them. This rebirth of the appellations started in the Piedmont and Tuscany in the 1980s perhaps and has slowly across the country and the South. What the producers featured in both books have in common is the importance of wine to express a place and not a technique or fashion. They also share a respect for nature and people, as well as the courage, conviction and confidence to pursue their vision even when others think it a folly.

“Altrove al Sud” explores the wine scene through different elements: culture, food, even politics. How does this confirm that wine goes beyond itself to become a means to explore the culture of a country, region, family.

Wine is a collection of human decisions made over time. It is called agriculture because it is culture that evolves with nature, humans and the local table. What we are seeing in new generation winemakers is not just a repetition of what Nonno did, but also a revisiting of how Nonno might have done things if he’d, say, had a little more space, a testing lab, a pump or the means to protect his wines naturally from oxidation.

After travelling southern Italy and writing this book, what is your feeling about the “new era” in the southern wine world? Is there a revolution here that is based on fundamentally new elements?

This is a golden age for wines in general. I think an important and fundamental change is that there are slowly more and more local-born Southern winemakers, oenologists and agronomists (and visionary entrepreneurs) staying in the South to pursue excellence. This is a revolution. It is no longer necessary to hire a miracle worker from the North to make good wine. Excellence in wine has evolved hand-in-hand with an awareness and renaissance of other local artisanal products: cheese, olive oil, salumi and more.

What are key factors this new wine generation is focused on. Are they unique to the southern culture?

I think throughout Italy the new generation is focused on sustainability and creating territorial wines that do what Italian wines do best: pairing with its unparalleled cuisines. This is not unique to the South. BUT, I think southern Italy has Italy’s most incredible range of flavors and cuisines. This is also true of its great wine diversity that is being rediscovered. Diversity and biodiversity are strongest in the South, where familial plots have remained small and resisted the consolidation of previous times that saw variation as a defect. Now differences are viewed as strength. Sophisticated urban consumers are open to experimenting with unfamiliar grapes with difficult-to-pronounce names even.

How has Sicily changed wine-wise and what caused such big changes?

I took a family vacation in Sicily in the summer of 2000, and at that time, it was hard to find good local wines served at a correct temperature in a restaurant. Wow has that changed! Now there are scores of good to great producers, and it can be hard to find a bad wine. Even local bar owners have wine refrigerators and can discuss the merits.The development of the wine country and culture (and hospitality) means that more young people can stay on the island and participate in the renaissance and are not compelled to leave to make a living.

In your chapter about Sicily you talk about Etna. Are the Etna wineries leading this revolution? How about the rest of the island?

Etna surely gets the most attention, as Alessio Planeta says in the book : It’s a dramatic image— a postcard. Etna benefitted because it is a densely planted area with a lot of small parcels and growers and producers. In the 00s you had a famous influx of “stranieri” who together with young locals created a “scene”. Scenes help accelarate wine quality, because people talk and the territory benefits from shared experience. There is only one harvest a year in wine, and when you are alone in a vast countryside, you are alone. Etna is a label that everyone over the South of Italy would like to emulate. But frankly the entire island has made incredible progress toward quality from Grillo in the west to Nero D’Avola in the east.

They often compare Etna with Burgundy. Do you think this the right approach or is Etna territory is so unique that it stands alone, requiring a different framework

Etna is unique. It is a live volcano after all—meaning the landscape is constantly changing. While Burgundy is also made up of small old parcels, its vineyard classification was set centuries ago. I am not a big believer in contrada susbstituting for “cru” as has been done on Etna, but I suppose it is a way to distinguish one producers’ wines from the other. Individual vineyards of different ages matter a lot on Etna to be sure as well as altitude and its position on the mountain. There is still a lot to be studied. For example, most of the talk about Etna wine focuses rosso and Nerello, but I believe that Carricante has an astounding potential as one of Italy’s great white wines that improves with age.

What is the international perception of Sicilian wine today?

The perception of Sicily in general is at the top of Italy today. The brand is perhaps second only to Tuscany (and possibly the Piedmont) in the minds of food and wine loving Americans. I just got back from a trip on the west coast of the US, and I think when you say the world “Sicilian” in context of wine, food, olive oil and they are “in”. Some of this may have to do with the fact that there are millions of Sicilian-Americans— many who travel to Sicily and have kept up with the changes on the island. The Sicilian diaspora can be a strength in the world.

Your book starts and ends with memories of your childhood in New York and Vico Equense. You recalled your grandfather as someone who had a big influence on your passion about wine. How would you characterize this writing style between memoir genre and storytelling?

I dislike the word “storytelling,” as its now used by every advertising agency to liven up press releases. Real storytelling means that you are willing to go deep (the writer and the subject) and tell the truth— both the good and the bad. The same is true with memoir, you have to tell the truth even the “bad” parts. Italy and the South is full of pathos and humanity which is the stuff of real stories.

You were born and raised in New York and then you moved first to France and then Verona. Southern Italy is without any doubt in your blood and soul. Which are the places you mostly belong to? Where is home?

Oh that is hard. I feel that I have pieces of me everywhere. The New York I was born in no longer exists. In France we lived near Nice (old Italy) surrounded by olive trees. I can no longer live without olive trees! I feel most at home in Italy. I love Verona, but I feel that when I travel south I am going to some ancient familial home. When I first travelled across Sicily (My father’s father was from Bronte) I had the very strange sensation that some family ghosts were watching over me even when I was lost in the countryside at night. It is the only place I have felt this so strongly.

Liliana Rosano