Modica, a city set like a jewel into a high plateau of the Ibleo mountains, rich in its millennia-old history and its gastronomical treasures, famous all over the world.

Modica divides up its countryside, a fertile one, with muragghiuni, classic dry walls, constructed without cement but only thanks to the patient labor of artisan stoneworkers. In the city, long staircases connect the houses of the central street of the lower city to those of the higher part, and then higher still, to the grottoes carved into rocky ridges. Once they supplied dwellings for the poorest part of the population, for animals, and also for bandits and fugitives. For example, in the quarter known as Cartellone, once occupied by the Jewish population, now brought back to life and a site which attracts many visitors along with the merely curious.

This is a city where strolling (“tampasiare”) is pleasurable and enjoyable, guided as it is by the fragrant aromas of stone ovens. Here “pani ra briula” (durum wheat bread), “scacce” (flat olive oil bread), pastieri, ipastizzu, la rota do caciu, “saimi” (biscuits made with lard) both for meals and on their own, milk biscuits, affucaparrinu (literally: priest-drowners), and fringozzi are produced.

What, then, can be said about the period in which local confectioners “atturravano” (toasted) sugars and pressed orange and citrons to produce sweets known here as “pietrafennula” (from pietra, stone in Italian) for their hardness and difficulty in chewing. Nest-like or cylindrical in shape, similar to the nougat found everywhere in Sicily, they were nibbled during the long nights preceding Christmas.

“Scruscio ri carta e cubbaita nenti” is a local proverb describing “cubbaita” (literally: rustling of cards and no cubbaita – more appearance than substance), an exquisite nougat of sesame seeds and honey which recalls the Arab domination of the island.

Modica unwinds along a main street once a water course along with small bridges which connected the two banks (to the point of earning the name of “the Venice of the south”), an avenue of churches, convents, and palaces once of the local nobility with typical wrought iron balconies, convex and bowed and sustained by “cagnuoli” (decorative figures in stone). The clock tower looms over the remains of the castle of the local counts, once the headquarters of political and economic power in the city. These beauties welcome and astound visitors. Scholars and intellectuals savor – becoming at the same time par -, the splendor of yesteryear through the stories, the tales, and the testimony of the period of the “gattopardi”, the powerful noble houses of the past such as the Grimaldi, the Polara, the Tomasi-Rosso, and the De Naro-Papa, just to cite a few. They dwelled in these palaces, lived both the ballrooms of grand festivities and the salons of conversation and conviviality, and filled the convents with the younger children, destined to a life of religious duties with or without the desire to actually live it.

And accordingly, in the silence of these monasteries, between meditation and prayers, the able hands of these brides of Christ prepared “conventual sweets”, small works of art which have come down to us thanks to the dolcerie, the pastry shops which still fill the streets of Modica through the sweet and marvelous transmission belt created by the monache di casa, nuns living at home. This was the name given to those who left the convents when they closed or definitively confiscated after the unification of Italy in 1860 and also to those lay figures who dedicated their life to Christ (for example, Liuna or the Avveduto). They visited affluent families during periods of religious festivities and there prepared palummette, quaresimali, nucatoli, mustazzola, biscotti da riposto, frutta martorana (imitations of real fruit but made from almond flour, similar to marzipan but sweeter), biscotti ricci, palmette, dolci savoia (lady fingers), dolcetti del conte, deliziosi, parigini, almond biscuits, known locally as “viscotta ra panza”, and the list could go on and on.

And it was precisely within the walls of the convents of the Benedictine nuns that the sweet which characterizes Dolce Modica, Modica the Sweet, was first created, something unique and inimitable. The “‘mpanatigghi” go all the way back to the pre-Columbian peoples of the New World, the Maya and Aztecs. The rite and consumption of chocolate arrived in Sicily through the Spanish presence in and rule over the island. The ‘mpanatigghia are ravioli stuffed with meat and chocolate and sweetened with cinnamon and cloves and then oven-cooked. It is similar to the “liccumia”, a sweet in which eggplant substitutes meat, which was unaffordable for the poorer classes.

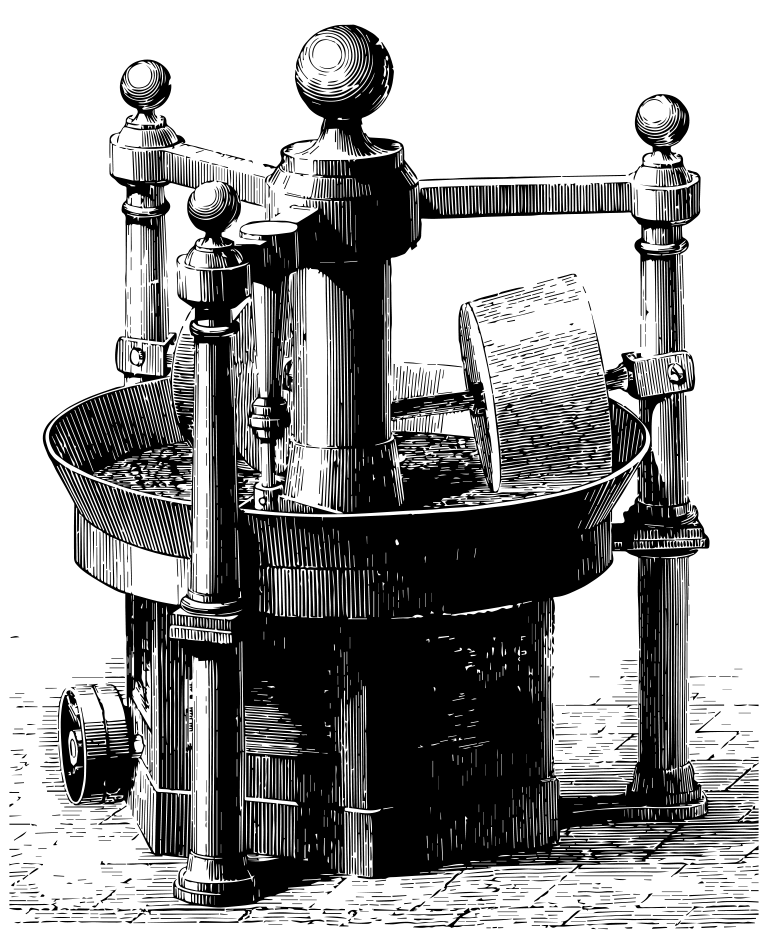

We are dealing with an authentic delicacy created by the nuns, invented to assist the preaching monks who wandered over long distances. The consumption of chocolate, in fact, was allowed by the Jesuit fathers even during Lenten fast days as it was considered a drink, not a foodstuff. The story of Modica’s chocolate was born in a cup: the “lanna ‘ra ciucculatta” (the metal recipient in which the liquid chocolate cooled and became denser). It was characterized by “sinna ‘ra ciuccullatta”, lines (signs) which indicated the appropriate unit of measurement for a cup of chocolate. Even today it is possible to purchase a chocolate pot with a pestle, a reminder of the “molinello”, a device which, twirled back and forth between the hands, helped to produce that dense foam so desired and appreciated by consumers of the beverage. In this way, all the typical aromas of the chocolate were concentrated along with – according to tradition – those of the added cinnamon, vanilla, and hot pepper.

Up until a short time ago, it was possible to watch the preparation of the raw material: the chocolate maker, kneeling and curved over a stone known locally as “a petra ra ciucculata” , a “chocolate stone” curved in shape and heated from below by wood and charcoal, worked the cocoa beans until they became a paste, bitter in taste, the departure point for the artisans of the trade. He then added raw sugar and the spices, for example vanilla or cinnamon. At the point, a delicious and highly fragrant mixture had been created, thanks as well to the secretion of the cocoa butter contained in the seeds. The artisan then proceeded with “u pistuni”, a large stone rolling pin, with which he performed the “stricate”, rolling the pin over the mass, once, twice, thrice according to what was necessary. The heat produced created sugar crystals which fused and became an inseparable part of the chocolate, creating little sparkling dots. This is the secret of this artisan-worked product which presents this shimmer to the eye, while the taste buds are stimulated by the textural roughness provided by the sugar, working together both with the bitterness of the chocolate and the overall fragrance, felt first by the nose and then in the throat.

At this point, the cooling phase was ready to begin: the chocolate went into the “lanne”, the metal moulds which were then banged against a table to empty them of the air which might have been absorbed during the various processes of the working of the material. After reposing for a few hours, the bars and tablets were removed from the moulds and wrapped in a type of oilcloth, pink in color for the vanilla-seasoned type, red for the chocolate with cinnamon.

The finest pastry shops and ateliers of Modica:

Antica Dolceria Bonajuto, www.bonajuto.it

Laboratorio Casa Don Puglisi, www.laboratoriodonpuglisi.it

Casalindolci, www.casalindolci.it

Donna Elvira, www.donnaelvira.it

Ciomod, ciomod.com

Sabadì e Gli Orti di San Giorgio, www.sabadi.it

Caffè dell’Arte, caffedellarte.it

- veduta di Modica dagli Orti di San Giorgio

- San Giorgio

- organo e interno di San Giorgio

- piatto di dolci

- Casaindolci, gli attrezzi…

- gli ‘mpanatigghi

- dolci alle mandorle

- veduta di Modica dagli Orti di San Giorgio

- veduta di Modica

- il cioccolato modicano con lo zucchero a vista

- Il tornio

- la materia prima, le fave di cacao

- lavorazione delle barrette

- lavorazione delle barrette

- la materia prima, il cacao arriva dal Sudamerica. Lo lavoravano gli Aztechi

- i nucatoli

- cubaita